I went to the footy on Thursday night. I left my house, turned right and walked towards the light towers. There were no other pedestrians about. There was no queue at the traffic lights in front of the bicycle shop. I didn’t see anyone parking their car urgently and with a bunch of children scrambling to put their scarves and beanies on. I was wearing my light brown cotton jacket: the same jacket I wore, adorned with player badges, on the day we won the 2017 Grand Final and the night we lost the 2018 preliminary final to Cox, Treloar, de Goey et al.

The fan shop at Punt Road Oval was closed. There was no one lingering about in search of merchandise and a good deal. The lights were off. A man on an electric bicycle hooned down the hill at 30 plus km per hour and almost collected me. He was enjoying his space: there were no fans, slowly enjoying themselves to disturb his fast and smooth journey home. Going up the slight rise, there was no din: no gently rising murmur of expectation, hope and enthusiasm. No chitter chatter between parents and children; mates and colleagues; casual acquaintances and strangers. A few magpies hung about, looking carefully for worms. They stopped and warbled. Their voices were so clear in the late dusk.

Footy without a crowd

Prior to leaving, a message had arrived in my phone: “do you agree with footy going ahead?” I had no immediate reply or no immediate thought about how my opinion or thought could matter. The question was a part of the general urge to work out the role footy plays in our life. The game, in this case, could be a welcome distraction from a general sense of fear and dread about the strength and duration of the pandemic. But this social function of being a distraction for us fans, means that others – players and staff – continue to work, imperilling themselves and perhaps further perpetuating the spread of the virus. I carried my phone in my pocket and continued to be ambivalent about the question. I could have gone either way.

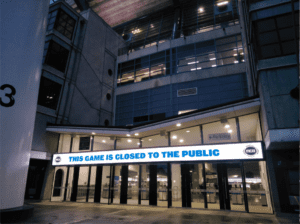

The concourse was as good as empty. A middle aged man and woman walked past, dressed in their sporty clothes. I saw someone wearing a Richmond premiership polo. I saw someone else wearing a Richmond jumper, riding his bike and making a video of the scene. I got up to the top of the stairs to the Bradman Gate. Here is where there is normally hundreds, thousands of people passing by, waiting for friends, queuing to go in, or on their way to other parts of the stadium. There was no shout of ‘Record’ nor any directions given from an MCG staffer telling us masses where to enter. “This game is closed to the public.” I could hear the pre-game pump up music as the players went through their warm up. The siren went. There was no cheering, shouting, booing or lambasting.

I continued my walk along the southern wing of the stadium. The sky was still and grey. The clouds were high. The trains trundled to and from Flinders Street. I walked to my favourite spot on the southern wing, where two grandstands meet and looked in. The players ran east and west. I saw Trent Cotchin and thought how well he was moving. I remembered that moment of seeing him kick his goal late in the Grand Final against the AFL’s Own Orange Team. How long ago that now seems. Out of view, Shane Edwards had either taken a mark or been given a free kick. The players cheered and ran back to the centre after he kicked truly. The first goal of the season. I saw the replay of his kick and the simple joy with which he celebrated: a smile and raised arms.

I wandered around slowly on the MCG’s perimeter and saw others taking photos and surveying the strange circumstances. I went home and turned on the tv. The commentators were trying to keep things normal and talk about the game. But, the unusualness of the situation was evident at every step of the game. I couldn’t get into it. And I didn’t want to watch it. Seeing the empty stadium only made me feel more estranged from a desired sense of normality and weekly rituals or habits.

Almost silent footy

The sounds of the game were clear. But, the clarity was haunting. The crowd is the space in which we bump into people whom we get along with and whom we don’t. Those whose perspectives we appreciate and those we disagree with. The noise of the crowd was replaced with the clear transmission of the players’ voices calling out to one another and cheering each other on. It was like being at a suburban ground. Only this time, the sounds were coming from the other sides of the Fortress MCG.

Footy can wait. This round of games has seemed like the last act in trying to maintain a charade of normality. So typical of the AFL: another act of folly.

*

Andy Fuller researches sports and urban cultures in Indonesia and Australia and is a member of the AFLFA Committee. This article was first published at Reading Sideways. The views in this article are his own and do not represent the AFLFA as a whole.